Robert Schatz: String Theory

Artist Statement:

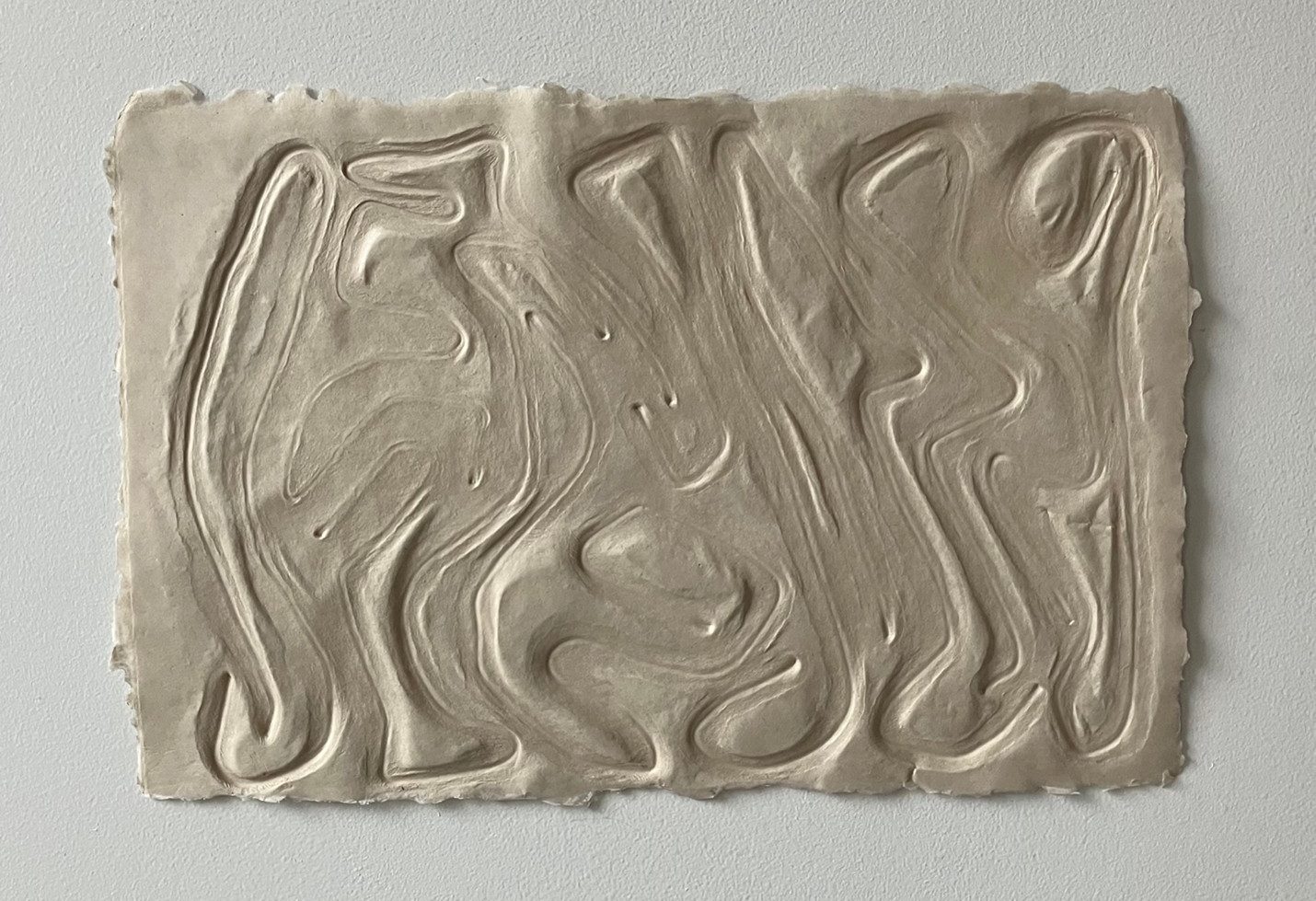

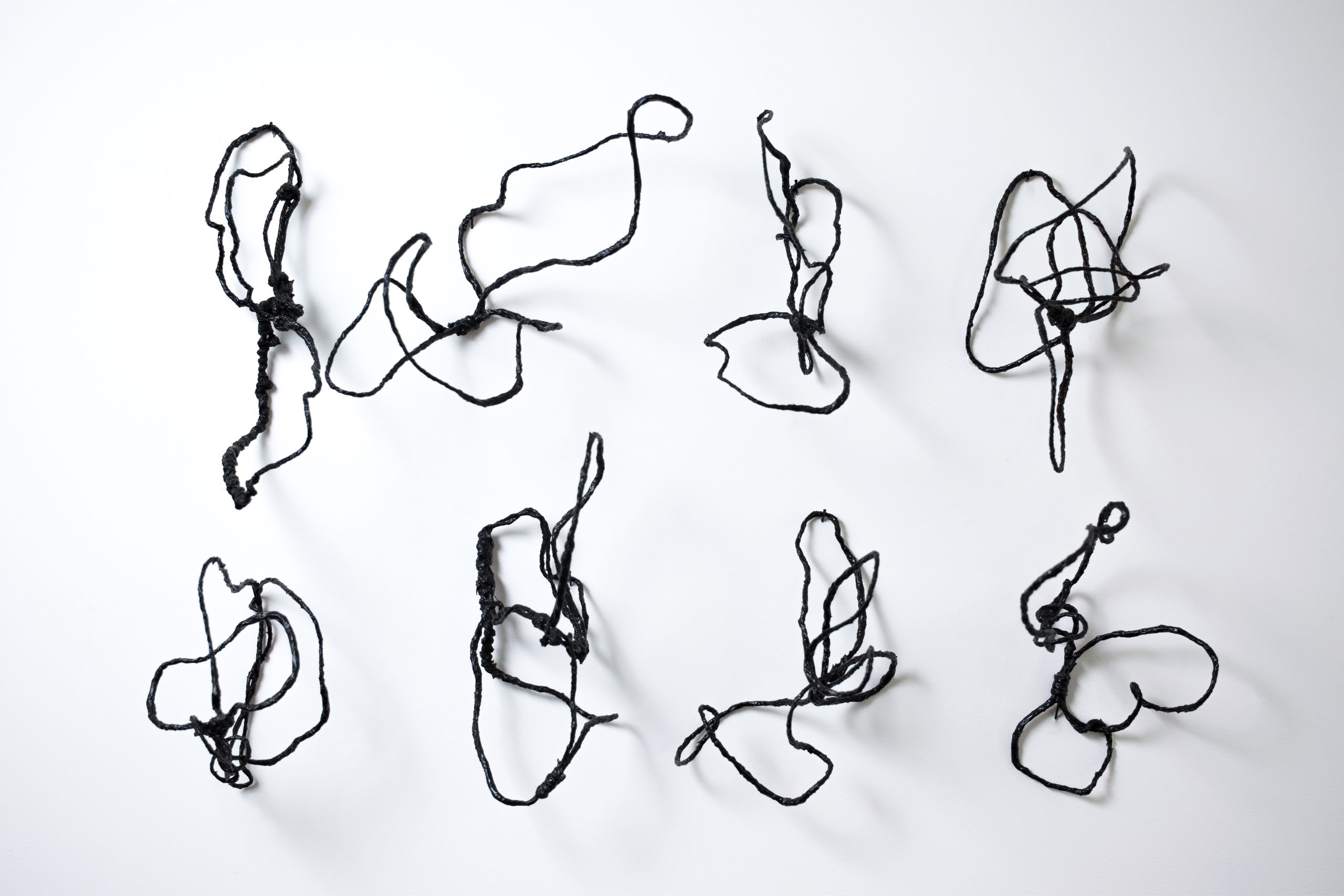

Manipulating humble materials intuitively and without preconceived composition, I build playfully enigmatic structures that perform like three-dimensional drawings moving through space in organic yet architectural ways. They serve, in their own fashion, as objects of meditation, partnering with their cast shadows to create a dance of form and non-form, evoking thoughts of Plato’s cave.

With philosophical affinities to traditional Chinese and Japanese art and urban graffiti, these works express my interest in line, dynamic structure, and kinetic space. They explore what the philosopher Alan Watts refers to as the “wiggliness of reality.”

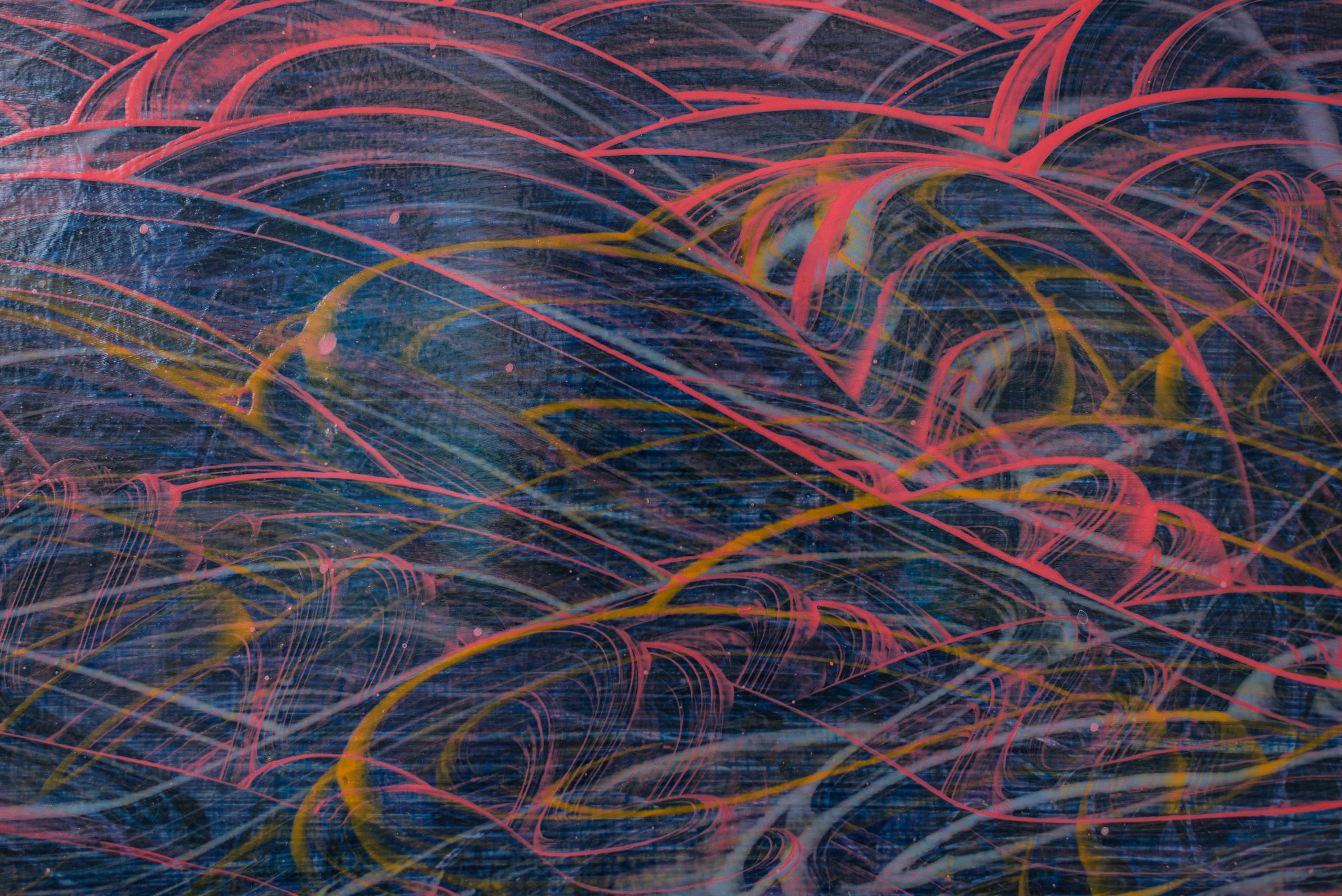

The sculptures are accompanied by paintings on paper, where brushwork suggests an unseen movement beyond the boundaries of the edge and hints at deeper realities behind surface appearances.

Q: What is the significance of physicality in your work?

Early in my career, through a study of Chinese calligraphy, I was exposed to the idea that line and gestural marking can signify the human body. This concept of embodiment is a fundamental aspect of my two-dimensional work, which is created through physical gesture and the movement of the brush or my hand around the picture plane.

When it comes to my three-dimensional work, the structures are emblematic of the body in that their lines and forms stand in for us as bodies moving through space. But, their physicality also elicits a physical response in the viewer. The movement of the eye, or the movement around the piece. The work generates motion, a kind of dance, on the part of the viewer.

Q: What are some of your primary influences?

My influences has been primarily philosophical rather than stylistic. I was first introduced to Taoism and Zen in the art history class. Their principles reinforced an already existing disposition in me that valued nature as a source of esthetic inspiration; not nature that is visible, but rather its processes. There is a “call for response” rather than an imposition based on a preconceived agenda. Taoism and Zen also taught me to accept so-called “happy accidents” during the creation process, to understand both the beauty in transience (echoing Heraclitus) and that life is a dialogue between opposites These themes became conceptual underpinnings for my work.

Q: In String Theory, what is the role of the viewer?

An artist obviously can’t control how viewers engage, but I would like to trigger a sense of play or whimsy; a curiosity – and at best – a kind of mythic feeling. So a viewer’s first response would spring from a sense of poetry, so to speak. And yes, since my three-dimensional pieces extend away from the wall into physical space, they are to be circumnavigated and viewed from multiple angles. The relationships between their linear elements change as a viewer moves around them.

I want the viewer to find a dialogue between shapes, curves, angles, axes of symmetry, as well as between cast shadows and physical structure. The open space of the sculptures also allows a kind of visual flight through the pieces, something I liken to flying among a bank of clouds. This moving through is also true in the paintings exhibited here. The viewer is looking through the white picture plane into a world beyond it.

About the Artist

Robert Schatz was born in 1958 in Allentown, Pennsylvania. As a young man Schatz studied at the Baum School of Art in Allentown. He earned a bachelor of arts degree magna cum laude in history and philosophy at the University of Scranton, then continued his fine art studies at Massachusetts College of Art and The Art Institute of Boston. He currently lives and works in New York, and from time-to-time has been heard playing the Appalachian dulcimer.