Buffalo, NY

2017

Type: Hotels / Reuse

Theme: Transforming Old Buildings

This project revives an architectural masterpiece—the long-abandoned former Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane—into a one-of-a-kind boutique hotel conference and event center, and Buffalo Architecture center. The 140-year-old former state hospital facility, originally designed by H.H. Richardson with a landscape design by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, was registered as a National Historic Landmark in 1986 and is regarded as one of architecture’s great 19th century treasures.

John Thomas Midgette

Project Manager

TenBerke

Design Architect, Interior Designer

Flynn Battaglia Architects

Executive Architect

Goody Clancy

Historic Preservation Architect

Simpson, Gumpertz & Heger

Structural Engineer

Buffalo Engineering, P.C. with R.P. Morrow Associates, P.C.

MEP Engineer

Watts Architecture & Engineering, P.C.

Civil Engineer

Andropogon Associates

Landscape Architect

Kugler Ning Lighting

Lighting Designer

H.H. Richardson

Original Architect

Fredrick Law Olmsted

Original Landscape Architect

Architecture Award

AIA National

Interior Architecture Award

AIA National

Honor Award

AIA New York

Excelsior Award

AIANYS

National Preservation Award

Driehaus Foundation

Award of Merit

SARA National Design

Excellence in Historic Preservation Award

Preservation League of New York State

Citation for Design

AIA New York State

Architecture Design Award

AIA Buffalo/WNY

Historic Preservation Award

New York State

Best of Year Award

Interior Design

Architectural Record

September 2017

Originally built as the Buffalo State Insane Asylum, the Richardson building exemplifies the typology of mental health institutions that arose in the 19th century. Despite the negative connotations of isolation and brutality that the name “Insane Asylum” suggests, these institutions were meant to be asylums, which in its original meaning meant a place of refuge and protection. They were self-sufficient institutions that valued community and signified a social acknowledgement and care of mental illnesses.

During this period, architecture and landscape were considered determinants of one’s health and potential means to cure the mind, so rigorous theories on the correlation between space and mental health were developed. Richardson’s design of the Buffalo State Asylum built on these theories, emphasizing the well-being of each patient, while Olmsted’s design complemented the architecture with informal and naturalistic features that provided what was considered a therapeutic landscape, which still retains some of its original form today.

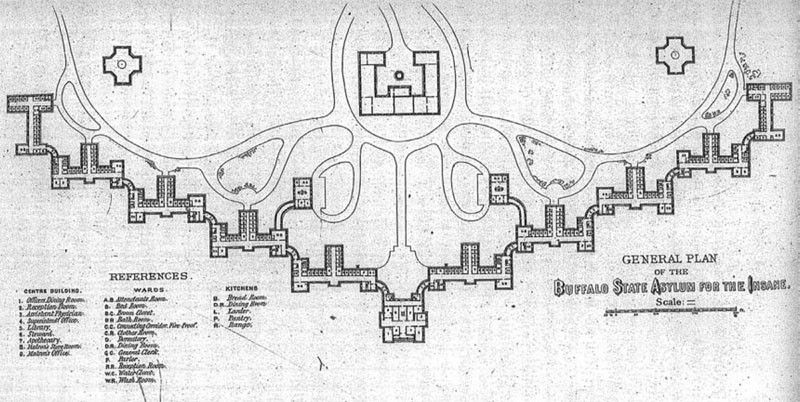

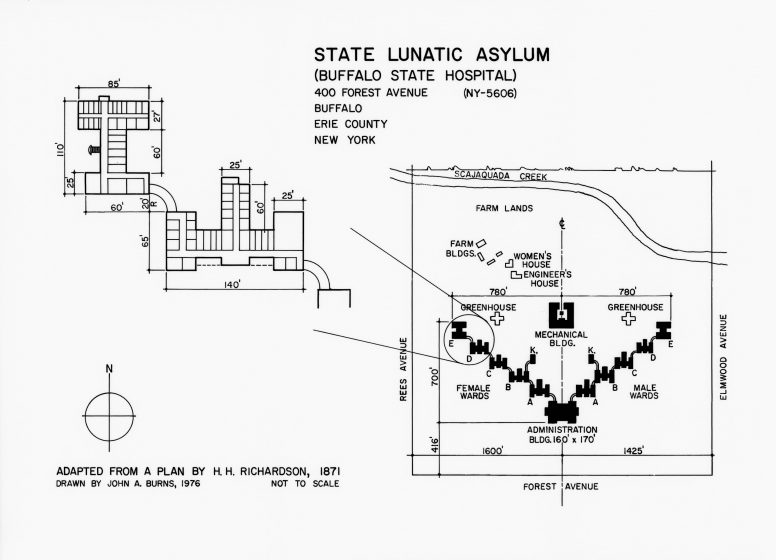

Richardson continued the work spearheaded by Dr. Thomas S. Kirkbride (1809-1883) codifying a formal typology for mid-19th century asylum architecture designed to improve the interior conditions for the patients. Kirkbride’s vision of an ideal asylum was a linear building, located in a remote, calming landscape.

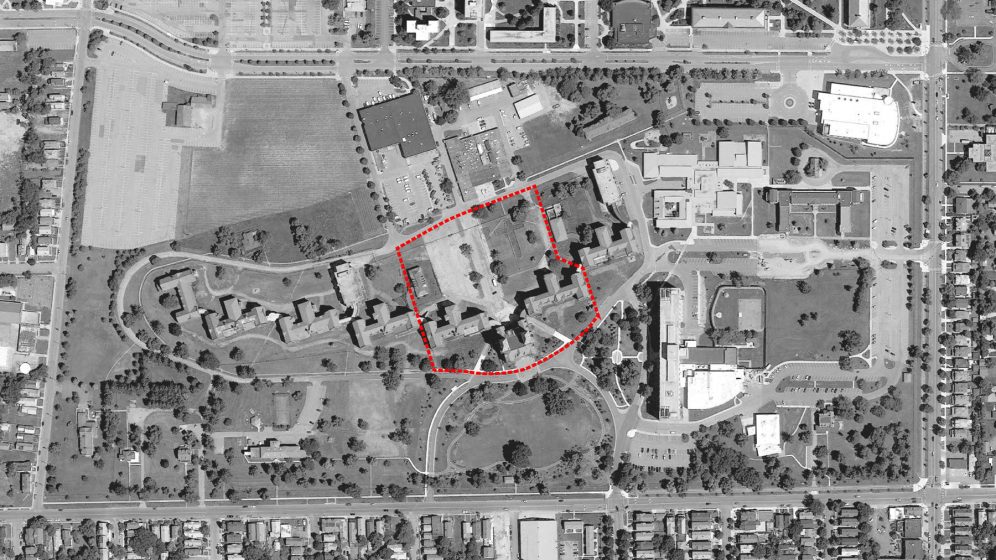

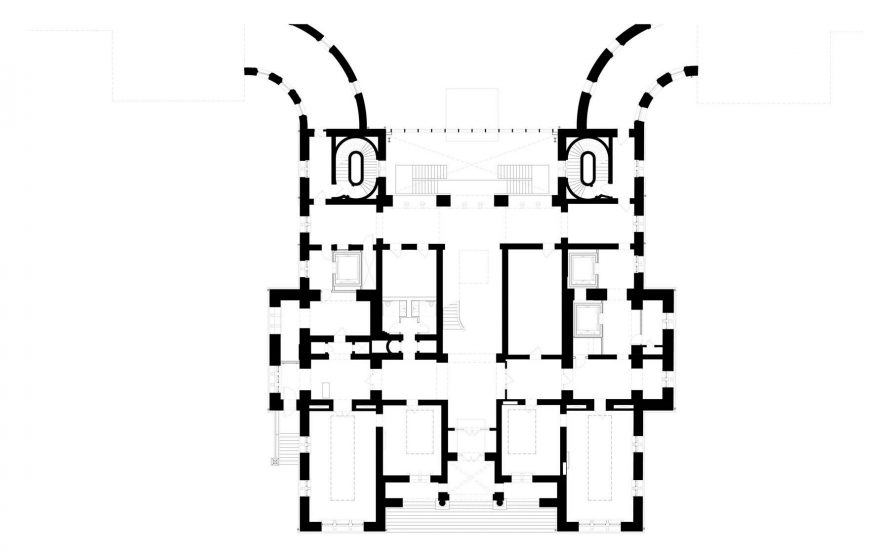

Functional programs were differentiated by composition: an administrative core flanked by two symmetrical wings of patient wards, each one recessing from its neighbor to form a shallow ‘V’ in plan.

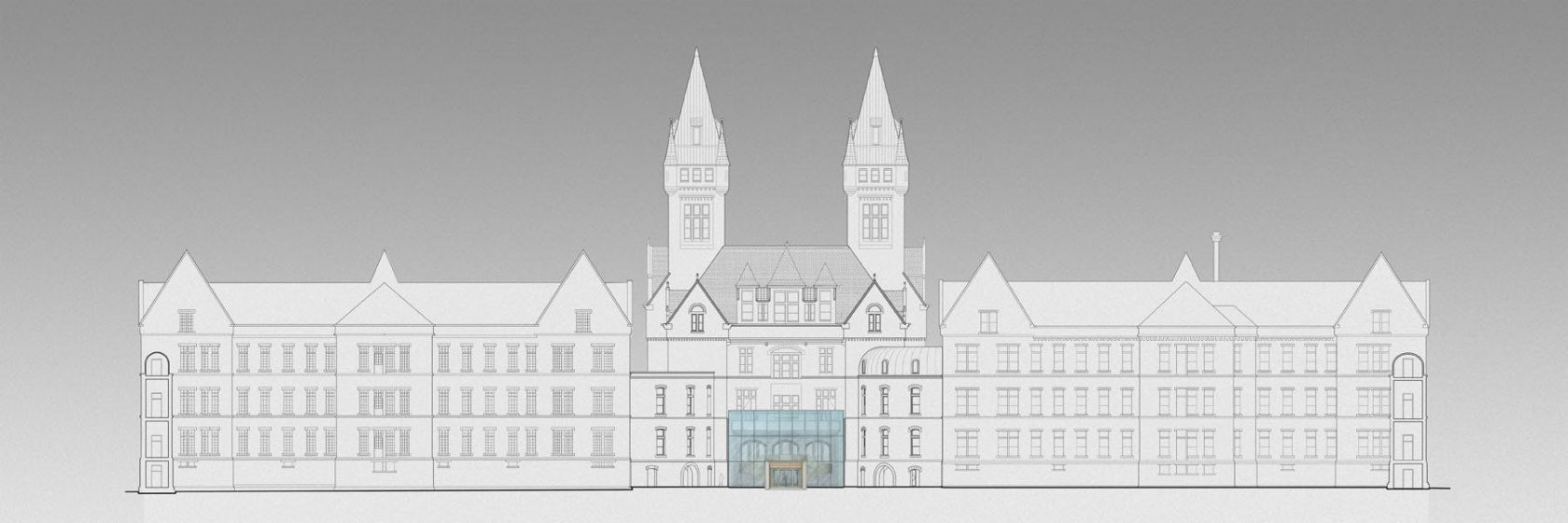

Richardson further developed the Kirkbride plan by offsetting each ward an entire building’s width, a choice that made each ward a functionally and formally independent unit with ample sunlight and uninterrupted views of the landscape. To counteract the distance, he connected the wards with curved corridors, masking the sprawl of the units and maintaining the unity of the complex elevation.

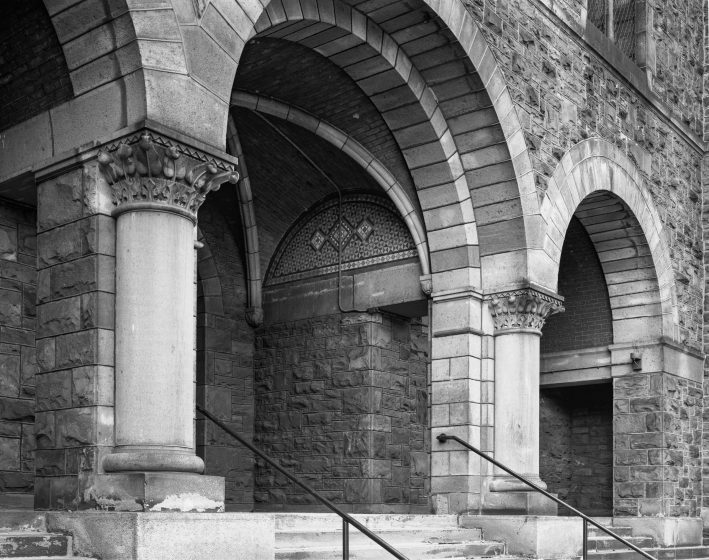

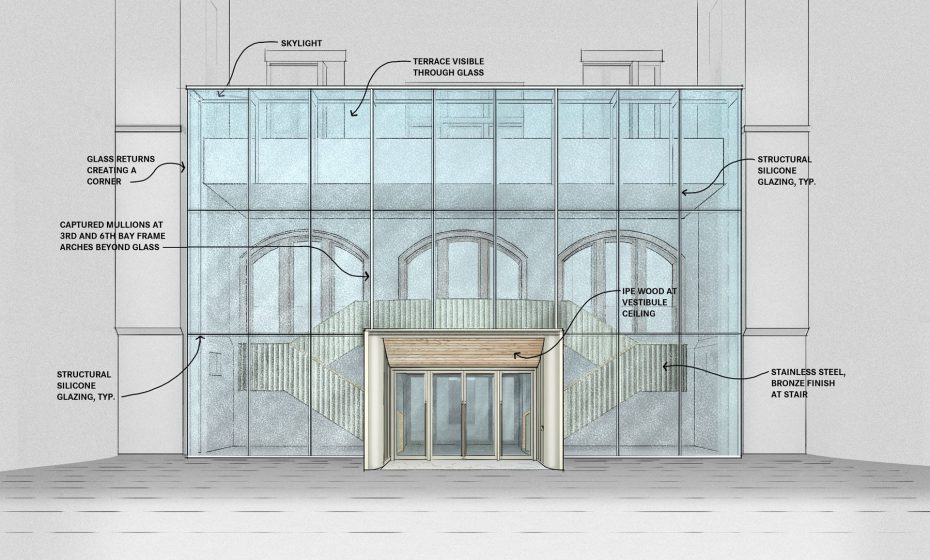

One of Richardson’s early works, this building bears many Richardsonian characteristics, such as the half-rounded arches in the entry logia with unadorned voussoirs and heavy piers. The charismatic Romanesque massing is enveloped by an austere, undecorated façade, a choice which resonates with Richardson’s own writing on his contemporary works: “the distinguishing characteristics of a style are independent of details; especially in this case in the Romanesque, which in its treatment of masses, affords an inexhaustible source of study.”

During the 19th century, three distinct landscape styles were formalized: the Picturesque, the Gardenesque and the Pastoral. Olmsted and Vaux chose the informal and naturalistic Pastoral for six asylum landscape designs, one of which was the Buffalo State Asylum. Olmsted and Vaux’s park-like design featured gentle topography, an informal pattern of driveways, asymmetrically seated architecture, and open views of the landscape, creating an ample outdoor ‘pleasure ground’ for patient care according to 19th century theories of therapeutic landscape.

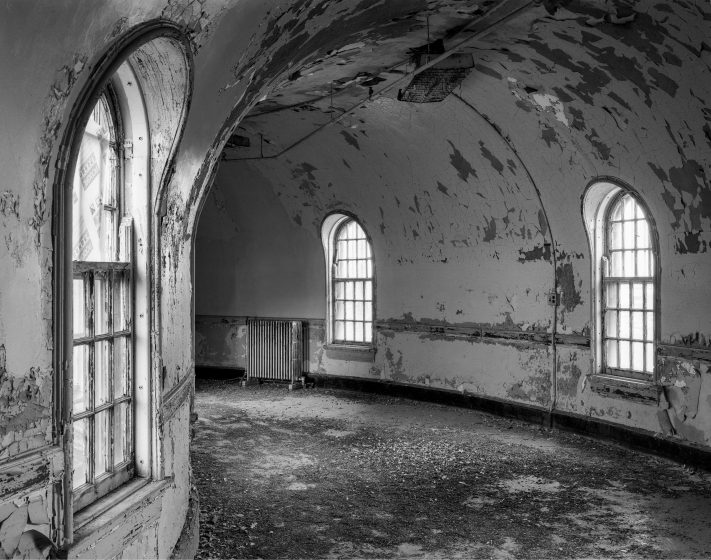

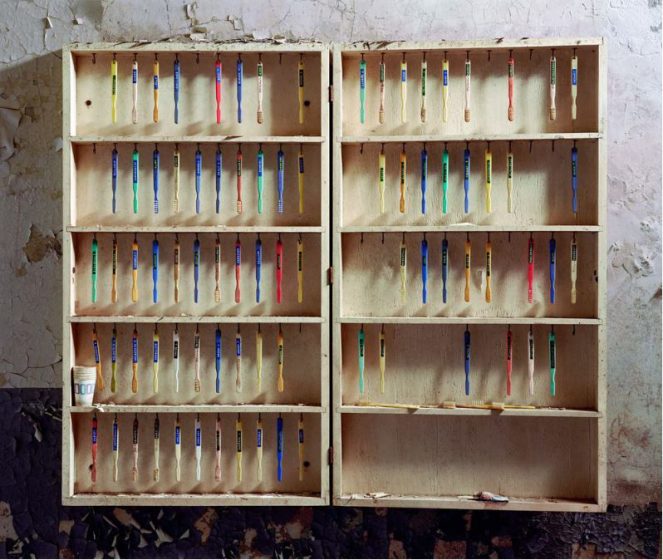

Photographer and architect Christopher Payne explored the Richardson campus as part of his work documenting abandoned and decaying mental health asylums across the U.S.. His photographs are stunning and poignant as they capture a “sense of loss” – The loss of society’s values that once considered these asylums “sources of civic pride;” the loss of the aspirations of architects and physicians who “envisioned the asylums as places of refuge, therapy, and healing;” and the loss of built records of countless daily lives that these buildings once contained.

His poetic photography conveys the lives lived in these forgotten structures, still tangible in the peeling paint and abandoned furniture inside the monumental exterior.